A deep dive into Paris Hilton’s Paris: The Memoir and documentary, This is Paris

CW: like every kind of abuse

Paris Hilton is about six months older than I am and I feel like we’ve been together for a long time. Back when I was a regular reader of US Weekly in the aughties, while simultaneously being a punk pseudo-anarchist wearing jeans as low rise as Paris’s, I was writing for the local alt weekly and becoming increasingly troubled by the emergence of P. Hilt, “famous for being famous.” I wrote an op-ed talking about how dumb it was to fixate on an heiress who did nothing. My newspaper was not interested in my hot take and my op-ed stayed buried on whatever hulking computer I was writing on in 2004, now surely occupying landfill real estate.

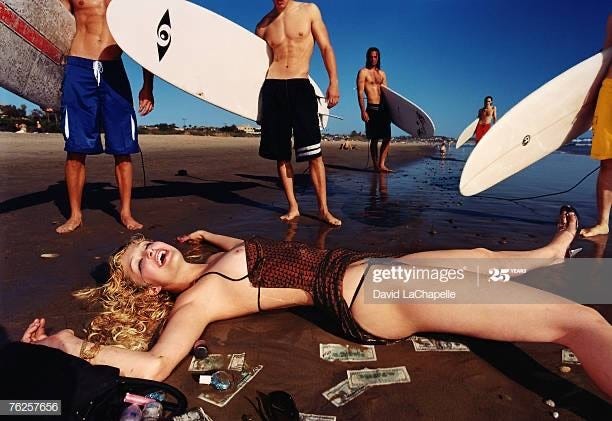

I’m not sure why I took such umbrage with Paris, in particular, except that we all did. She was a rich dumb blonde with a sex tape and a tiny dog in her purse, who on her new reality tv show said she didn’t know what a Wal-Mart was (“is it a place to buy wall stuff?” she asked a table full of people from Arkansas). A guy I knew watched her sex tape, (the brutally titled 1 Night in Paris), which we all thought she leaked on purpose to get more famous. “She watches herself in the mirror the entire time,” he told me from atop his tower of high moral standards, “she’s completely obsessed with herself.” But I also simultaneously kind of liked Paris, she seemed like a bitch who didn’t give a fuck, I wanted her pink razor phone. I saw a photo of her walking down the street in a tee which stated “Team Jolie” at the height of the fervour against Angelina for running off with Brad and thought it was funny. She was tall and thin and blonde and beautiful and astronomically wealthy and would never have to work, just party. She was a lightning rod for curiosity and envy. You were jealous of her, you hated her, you wanted her punished for the crime of her luck.

Around the end of the aughties, as the Kardashian star was in its ascent, I heard a clip of an interview where Paris was asked what she thought of Kim’s newly famous butt and she said it was “gross”, like a “big trash bag filled with cottage cheese”. Kim being her mousy former assistant, recently the subject of another leaked sex tape. And I thought, ok, someone’s a little salty she’s being eclipsed. Because Kim and her family did eclipse Paris, you stopped really hearing much about her, new people were famous for being famous now, plus there was Instagram. The whole world was full of Paris replicas, posing and preening their way to social media domination. Her script had been copy/pasted and expanded upon. Here’s an interesting article about why her power wained as what we wanted from celebrities grew more personal.

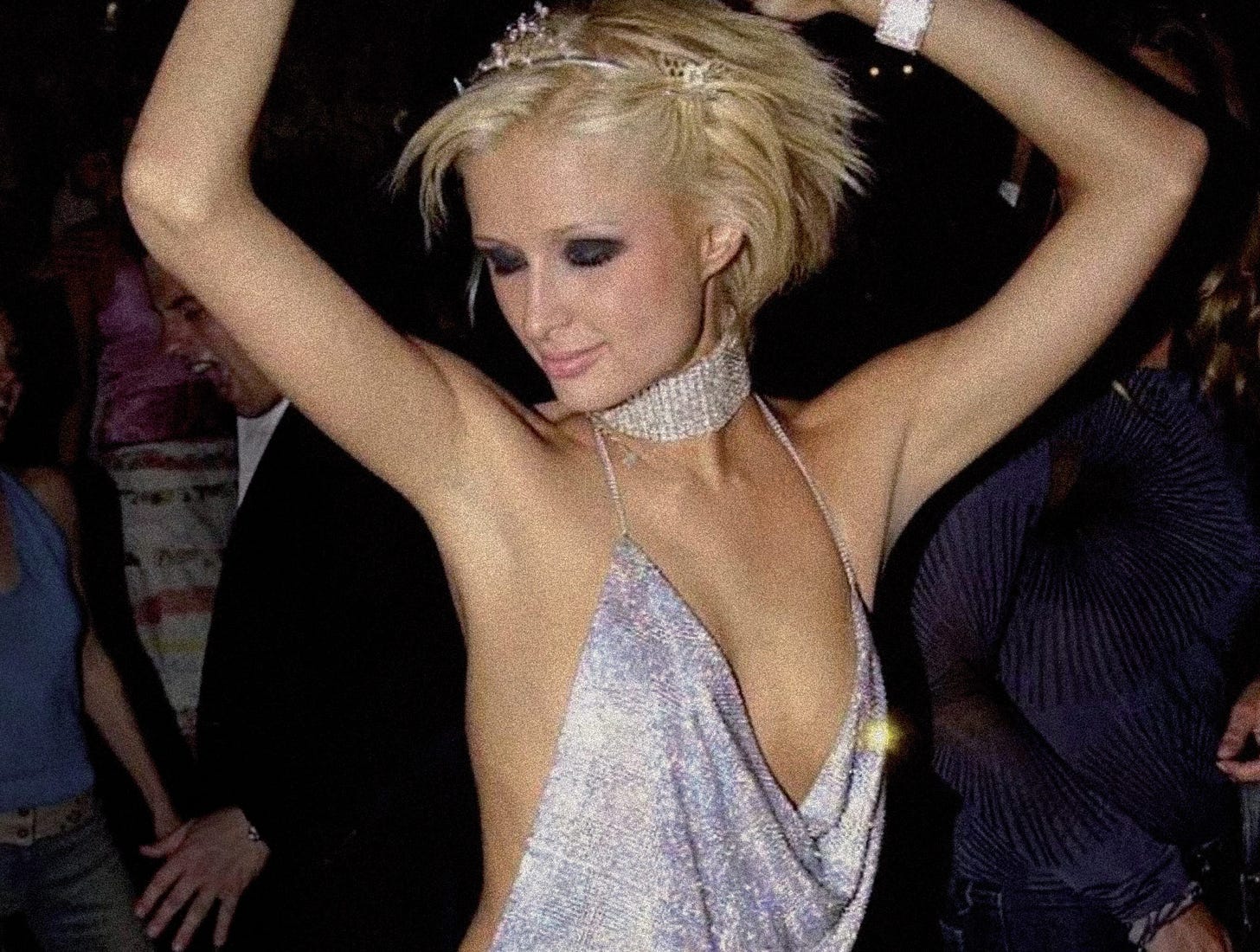

I heard that Paris was DJing, assumed she had die hard fans who were doing things like going to these shows and buying her perfumes or athleisure or whatever she was selling that I didn’t know about and wasn’t interested in. The only time I remember seeing her in the teens was, interestingly, dressed up as Kim in an Yeezy campaign (which honestly seemed like a publicly enacted revenge fantasy for Kim more than anything else). Paris represented a particular time, the aughties—velour tracksuits and hip bones, barbie pink, sparkles, exposed midriffs, boot cut jeans, choppy bleached hair, high gloss lips, fake tans and iridescent make up. She represented how we talked about and viewed and judged and aspired to be women then. There’s a lot more to be said for re-examining how women were treated during the aughties, which I’m not going to get into, but can be read about here.

The documentary This is Paris, was filmed in 2019 and premiered on YouTube during the first year of the pandemic. It’s directed by a journalist named Alexandra Dean who also did an acclaimed documentary on Hedy Lamarr. The documentary and Paris: The Memoir, released in March of this year, are very much connected, with Paris in the book even recounting verbatim things she said in the documentary. You can’t discuss one without the other, imo. The book is clearly the flood waters rushing out after the documentary burst the dam.

The memoir was written with assistance from celebrity ghost writer Joni Rodgers but the heavy hand in the memoir is Paris’s own. Compared to the documentary, it’s very muddled and confused in tone, Paris clearly struggling to let her branded identity fall away. In 2004 Paris put out a book called Confessions of an Heiress: A Tongue-in-Chic Peek Behind the Pose, which I did not read but nonetheless felt the shadow of here, Paris unable to stop herself from throwing in girl boss platitudes and pat declarations like “I was born in Louboutins,” which contradicts the messages she is otherwise conveying. I sensed a fear of letting down her fans, of letting the veil fall away, though at the same time, attempting to set the veil on fire.

The documentary, in the hands of someone else, an observer to make the editorial tough calls, is much more successful in putting across the point I believe Paris, at times in her memoir, is floundering with—that she is not her persona, that the persona has been a deliberately built purposeful thing, a maintained thing, a thing she battles with internally. Though the book is much, much more explicit than the documentary, if you had to choose one to engage with, This is Paris shows more of the strain, the cracks at the edges. I will discuss both the documentary and book in tandem.

I picked up the memoir on Audible randomly, which Paris reads herself, because I thought it would be like full of like, aughties celeb gossip or something equally light. I had not heard anything about it and did not read anything about it in advance. Paris goes hard right off the bat into how her understanding of herself changed with an adult ADHD diagnosis and I thought maybe that would be the framework for the memoir. Paris wants you to know she is smart but no one diagnosed girls with ADHD in the 90s, so she struggled in school, acted out. But the heart of the memoir, and what it spends the most time on, is her history of extreme and graphic abuse. She is very indecisive about calling out her parents for their part in this. Every time she brings up something fucked up they were involved in she couches it with saying she loves them so much and they’re so wonderful and would never hurt her on purpose. I kept wanting her to get therapy and then try writing this again. I wanted to take her by her shoulders and say, but they did hurt you. They hurt you a lot. Repeatedly. There was a line to walk by which she could have held them accountable but not trashed them. However, the memoir just gives a sense of hyperventilation— wanting to say what she needs to say, terrified to own the consequences of saying it.

As a tween Paris overhears her mom in another room reading from her diary out loud to her aunts in a high, stupid voice, who are all dying of laughter. I was like, cool, five star parenting, Kathy Hilton. This is not long before Paris is groomed by a teacher at her junior high, who lures her into his car one night outside her house and makes out with her. Her parents catch them in the act and, afraid to sully their name, do not pursue any action against this teacher, but instead blame Paris. They send her to live with her grandmother for a year while they all move into a suite at the Waldorf Astoria. This becomes a repetition, Paris is bad, Paris is banished. While living with her grandmother, she and a friend go to the apartment of some guys they meet when unsupervised at the mall, where she is raped, which she never tells anyone about. Then she is kicked out of a lot of schools, she can’t sit still, she can’t focus. When allowed to return to her family, she loses herself in the 90s NYC rave scene, sneaking out at all hours to dance. So her parents have her kidnapped in the middle of the night and taken to a “school” for “troubled teens.” She shrieks for someone to help her as strange men drag her out of her home and no one comes. She spends two years at these facilities, she runs away from them all and is put back and back and back.

In the memoir she recounts the moment in the documentary where she tries to tell her mother what really happened to her at those “schools”. She says her mom starts to lose it for a moment, lowers her face into her hand, but when she raises it again, Kathy’s face is mask-like, “she looked pretty,” Paris says. The documentary was not intended to expose Paris’s connection to these troubled teen facilities. Paris and her family have spent twenty years saying she was at a boarding school in London for high school, when in truth she has never graduated from high school. Alexandra Dean followed Paris for a year on her round the world non-stop DJing and product launching gigs, and they started discussing why Paris never slept, never wanted to fall asleep, was in her late thirties partying until dawn like she was nineteen. “I have nightmares,” Paris said, “that I’m pulled out of bed in the middle of the night.” When she confronts her mother, to say that she’s going to talk about what really happened to her at the correctional “schools”, Kathy regards her with the only expression she ever seems to make when looking at her—tense suspicion mixed with defensive amusement. “What really happened?” Kathy says, her voice touched with anger. Paris lamely names a couple things, she was strangled, put in solitary confinement, hit. Later on in the documentary, after a disturbing scene where her drunk boyfriend tries to sabotage her DJ gig at some big music fest, Paris is decommissioning her laptop. She says she always does this after leaving a relationship because men get controlling in her experience, they hack her, among other things. What other things? Alexandra asks. Paris says she’s been in five different physically abusive relationships. She thought for a long time that extremities of emotion equaled love.

What happened to Paris at these schools is like nothing I’ve ever heard before. I didn’t know these places existed or that these things happened. These places tell parents their children are violent, pathological liars, so that nothing the kids say is believed, they ask parents to sign over all medical rights to their children, saying this is their child’s last chance. However, I’d like to imagine if my daughter told me fucked up things were happening to her, so much so that at one point she runs away and is so afraid to go back she hides inside the ceiling panels of a random restaurant, as Paris did, I would reconsider things. Children at these schools died. They were under nourished, fed rotten food, dehydrated, used for hard labor, punishment often involved sleep deprivation or naked solitary confinement. Girls were woken in the middle of the night for regular “gynaecological” exams. They were not allowed to cough, to look out windows, to use mirrors, to wear their own clothes. They were encouraged to snitch on each other, called numbers instead of names, beaten, smacked, choked. They were watched and cat called by staff while showering. They were injected with substances to make them compliant. They were forced into “group therapy” sessions where they had to spend hours hurling the most vile abuse they could think of at each other, egged on by staff, until they broke down, and afterwards to “smush”, which meant to lay around and pet and stoke each other (and staff) also for hours. I am surprised that Paris survived this, I am surprised anyone survived it and my understanding is that suicide, during and after time spent at these places, was common. Advocates against these “schools” have compared them to the Stanford Prison Experiment and said that these students are stripped of their human rights. Both in the documentary and in the memoir Paris says repeatedly that she does not trust anyone, including her own family. However, she also doesn’t trust therapists and has never seen one. So, because of her level of fame, she relies on her family, that she doesn’t trust, for support.

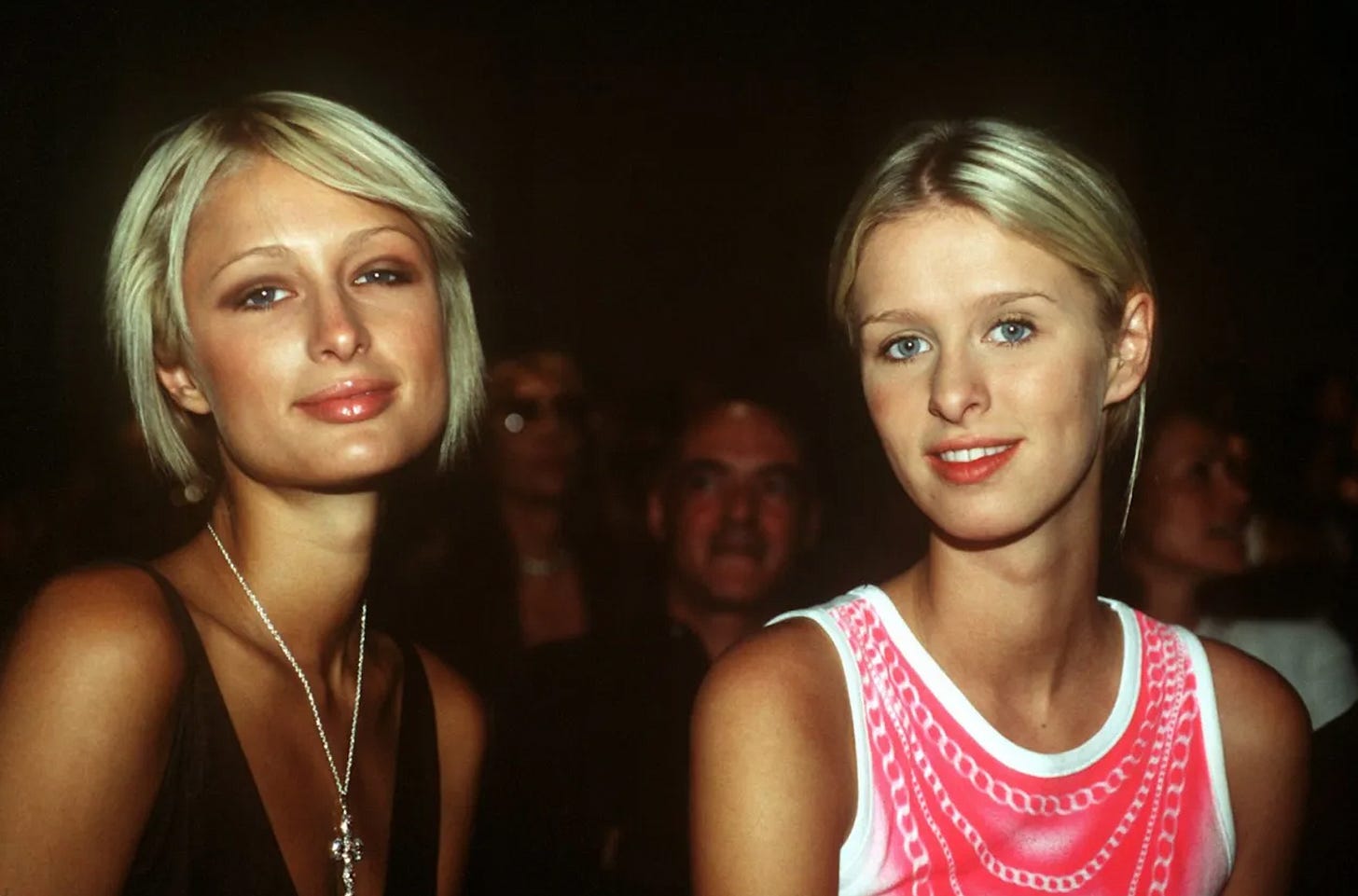

My summary above barely touches what happened to Paris when she was at these facilities. Her recounting takes up the majority of the book. Towards the end of the documentary, she meets with other survivors from the reformatories and at one point becomes so overwhelmed she escapes to go stand alone in her closet for awhile. Alexandra follows her. Paris, seeming both exhilarated and panicked, says she is starting to remember who she was before the abuse. She looks around in bafflement at the clothes and shoes surrounding her and says, “none of this is me, I don’t care about any of this shit. I like to be at home in sweatpants and sneakers.” Nicky, Paris’s younger sister, clearly the family golden child and good girl, is steely eyed and almost hostile when interviewed for the documentary. “I have spent twenty years avoiding being interviewed like this,” she tells Alexandra frankly, “but I’m doing it because no one knows Paris better than I do.” She talks about her tomboy older sister who wanted to be a veterinarian. She says Paris would prefer to be at home with her dogs, working on her scrapbooking and collages then galavanting around the world as a professional blonde. Her Aunt Kyle, when interviewed, says she feels too much focus was put on Paris’s beauty in childhood. In a home video clip, a ten year old Paris is asked if she thinks she is beautiful. She turns to pick up her pet rabbit and holds him up, “he is,” she says.

Paris felt a drive after leaving these facilities to make as much money as she possibly could so she could insulate herself in safety and control. Paris’s public face since then has been wholly aspirational—she is nothing if not unbothered, moisturized, happy, focused, flourishing. Paris built her brand, her persona, to protect herself, to hide what happened to her and now she can’t escape it—it makes her the money she wanted, but it has also eaten her. Throughout her audiobook she goes in and out of baby-voice whenever she seems too close to letting the persona fully fall away. She says she invented a new art form, proudly claims the title of world’s first influencer and calls herself a performance artist. She rhapsodizes on all the self expression influencer/selfie culture has allowed (to which I made this face : / while listening). The Paris in the documentary is less affected, however. She says she’s worried about influencer culture, social media, the damage it’s doing. “Do you feel responsible for it?” Alexandra asks her. “I do,” she says, grimacing.

She addresses the sex tape in both the memoir and the documentary. In the book she speaks of it flatly, exhaustedly. In the documentary she is openly emotional. I got the sense that when Paris speaks for herself, she is in turmoil, unsure what line to toe, usually reverting to predetermined statements and characterizations. But when questioned by someone else, the experience of being seen often unmoors her. The sex tape is another violation, another rape, she was nineteen and in the thrall of a much older man. Paris, who as a teenager was locked away in a place where she was denied any self expression, even a mirror, and told daily what a worthless whore she was, came back out into the world with a thirst for her own image. She loves (or loved) being perceived as a sex goddess, as an object of desire, she was happy to play into it, to own it, to revel. However, the abuse and assaults took their toll. She says she thought women were joking for most of her adult life when they discussed having orgasms, she had no idea what they were talking about. She identifies as mostly asexual, though as a young adult she didn’t have the language for it and found herself and her partners constantly frustrated. Newly married, Paris says her husband has tried harder to understand her than any man she’s ever been with and she “likes hooking up with him.”

I watched some clips on YouTube from her recent E! reality show Paris in Love that follows her around over the months preceding her 2021 wedding. It’s entirely different than the documentary. She’s wearing like a pound of makeup in every shot, often hidden behind sunglasses, talking in the baby voice, seeming frightened and stilted whenever she’s supposed to be engaging in some open moment of Kardashian-like on camera vulnerability—ditto for her family members. A scene where she’s supposed to be chatting with sister Nicky on a bench in a park about the healing she needs to do comes across so badly forced they seem like strangers, dress up dolls, fumbling for something to say to each other while the cameras watch. At the end of the documentary, Alexandra asks Paris, “do you think you can break up with your brand now?” and Paris laughs sadly and says, “no…it’d be an expensive divorce.” Expensive in many senses, I expect, perhaps the most emotionally. She says she’s giving up the act, the persona, and I believe that she wants to but also that she doesn’t know how, or can’t access, the ability to.

Unlike the documentary, I don’t think Paris: the Memoir is a success on the whole. It’s too confused about what it is doing, it tries to both transform her and keep her fixed in place. It should have been solely focused on the abuse and how it has effected her, rather than trying to shoehorn in quirky details about the rest of her life and do fan service. However, that doesn’t mean I don’t think there’s things to take seriously about it. Top reviews for the book on Google disappointed, and at times, angered me. The one in The Guardian eviscerates her, refuses to even acknowledge her abuse at all, referring to it only once in passing, mentioning she attended “a reformatory for bratty teens.” The Jezebel review, when discussing the teacher who groomed her, puts the word “pedophile” in quotes as though Paris Hilton was born, like Venus, out of the sea, fully mature. Like I’m sorry, but is an adult man making out with one of his eighth grade students not the kind of situation the word pedophile was intended for? Many of these reviews state directly, or strongly imply, she wrote her memoir as a calculated move—riding the wave of #metoo into a rebrand which will frame her as a successful business woman instead of a stupid blonde.

In my opinion, 2023 is not exactly cresting the height of the ever waining #metoo movement, the coffin nail was pretty firmly hammered in on that one with the Depp vs Heard trial last year. Also wasn’t the whole thing about #metoo that any woman could be abused and be free and supported to discuss her abuse? It wasn’t a “no sluts allowed” club, the entire idea of it was that it was literally for everyone and that abuse occurred on every level, and to one extent or another, to every woman. Additionally, it doesn’t make sense to claim Paris Hilton is the dumbest bitch to ever live but simultaneously so wily that she is going to harness a cultural movement so she can rise like a phoenix from the ashes of her irrelevance. That’s just misogyny, my friend. I do think there can be duplicitous people who take advantage of current cultural mores or trends to make headway for themselves, but I don’t think that’s what is going on here. I also think finger pointing or focusing on what unworthy person or two might slip by during broad social change, that is generally beneficial for everyone, is corrosive.

Interestingly, Goodreads, often rewarding the most negative reviews, was more open to Paris’s memoir. One review states: “the biggest issue I had with this book is that it lacks all of the balls that 2004 Paris had…what made Paris interesting back then was that she was no cinnamon roll of a person. She was not a nice girl.” The professional reviews, however, feel that Paris is not apologetic enough for the numerous racist slurs and bigoted statements she made in the aughties, or for her support of family friend Donald Trump in 2016 and her family’s conservative politics. In the memoir she, indeed, does not get into specifics but says that the abuse at the correctional schools, where every student was constantly berated in the most graphic language possible, numbed her and that in her twenties her PTSD was pretty bad and she made a lot of stupid choices and hurt a lot of people. She says it’s not an excuse for what she did but context. She is no longer the provocateur the Goodreads reviewer found so intriguing but she is also not groveling for forgiveness. And she is so derided a celebrity I doubt the groveling would do much to change what people think about her.

What I saw here was a woman in her late thirties, starring down forty and asking herself what the fuck happened in her life. Why did she never get married? Why did she never have kids? Why does she travel 300 days a year? Why can’t she stop partying? Why doesn’t she have long term relationships? Is she going to live the rest of her life this way or does she want something else? And, that, to me, seems normal. That asking these midlife questions would unpack her trauma, also normal. That she would want to speak about it, as a public figure, to both explain herself and maybe help people, also normal. She doesn’t need to rebrand herself as a successful business woman, she already is one, she has some billion dollar empire of products in Asia and has for like fifteen years. I didn’t go through what Paris did, but I don’t doubt her trauma or PTSD. At one point she talks about the abandonment by her family, that her heart beat asked “Mom?” every second she was alone and in pain. I, myself, have had a very similar experience.

On a certain level, I believe everyone deserves redemption. And that redemption is part of the human experience. It isn’t granted to one, like a crown, but earned through work. It’s messy and circuitous. Redemption isn’t something anyone gives you, it is something you give yourself by allowing yourself to become unstuck, to live in and accept the rapidly flowing, non-linear confusion, and often horror, of your own life. I think it’s worth allowing people to try and do the right thing for themselves and others, rather than holding them endlessly on trial for their past crimes. Are there exceptions to this? Yes. But that isn’t the point. The thing is, we can’t choose who will hit the wall of self realization and crisis and who won’t. No one can make it happen for themselves or for anyone else. You can’t cherry pick who your preferred people are in the world to have dark nights of the soul.

Surely we have all known someone who we wanted to be a deep pool but who turned out to be a two inch puddle, and someone we discounted, disregarded, disliked, who then surprises us with depth or capacity for change. There were many times I wanted my life to be different but didn’t want to experience any more pain, so I remained where I was, nothing could have gotten me to do otherwise, not even my own unhappiness. But then one day I said, ok, I want to open the cellar door and see what’s in there. I’m not sure why it happened when it did, it just did. Paris Hilton, this beautiful, incendiary clown, could have lived her entire life almost completely unknown to anyone, covered as she was, and is, by the thick fondant of her persona. But for reasons she has perhaps made public by the works considered here, or is keeping to herself, or which are unknown even to her, she has decided to peel back the bandage over her wound and look at it. I think we should take it in good faith that such an action is not one calculated by a megamind barbie who should never be allowed to exist outside of 2005, but is simply human. That Paris Hilton is as human as the rest of us.