Sad

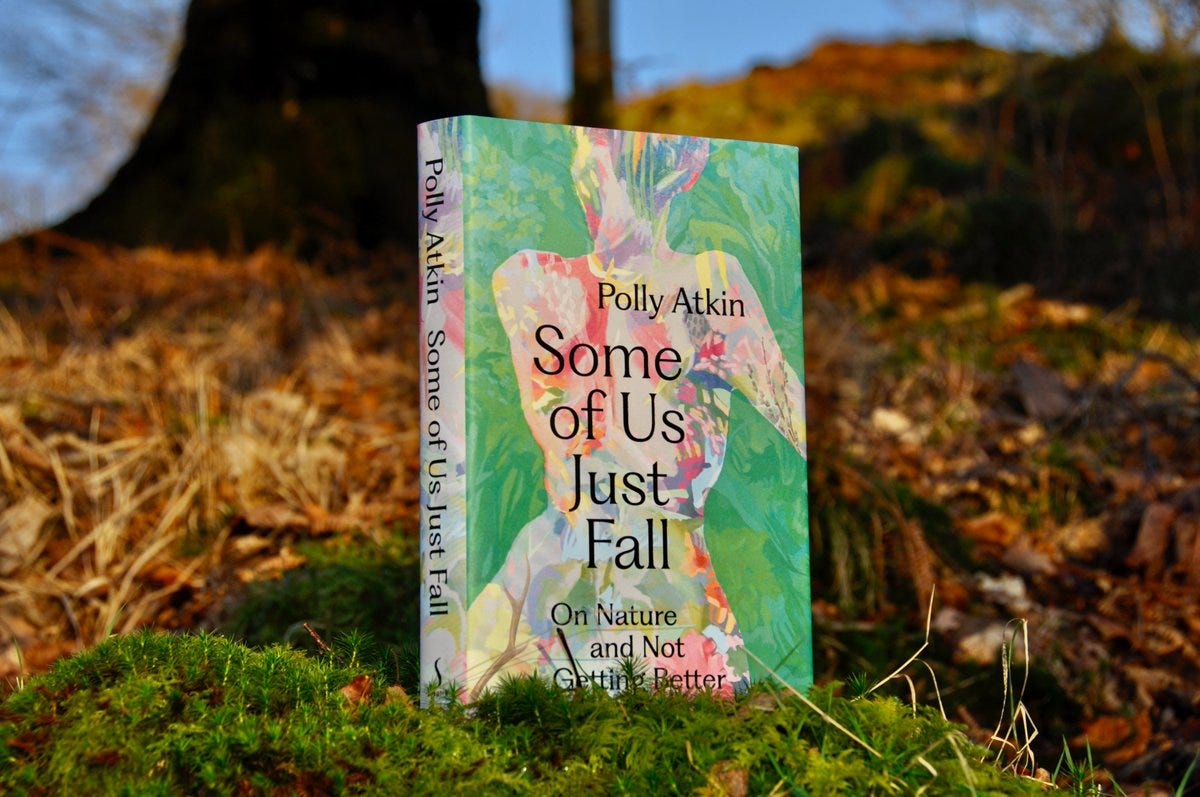

I don’t read a lot of illness memoirs, they are something I touch on only very occasionally. In times of poor mental health I can be hyper vigilant about body stuff and reading all the ways someone’s body has gone haywire can be upsetting for me. And the rest of the time, I am too busy being sick! When I pick up a book I want an escape from illness, not more time thinking about it. However, Polly Atkin’s Some of Us Just Fall with it’s beautiful title and cover sparked my curiosity. Indeed, some of us do just fall. Additionally, I liked its subtitle, On Nature and Not Getting Better. That’s promising, I thought, no one is going to blow smoke up my ass about positive thinking or one weird trick that healed them or how they ate/prayed/loved to perfect health, run a popular Instagram account out of their van, wear turquoise jewellery and sell classes on meditating. Not getting better is something I know a lot about. Once I started reading Some of Us Just Fall, I had to force myself to put it down just because it was so gorgeously written and full of powerful insights that I wanted to savour every bit of it instead of tear through it.

Atkin suffers from hypermobile Ehler Danlos Syndrome (hEDS), a connective tissue disorder, and Genetic Haemochromatosis, a metabolic disorder that leads to toxic iron accumulation. Like Fern Brady, who will be discussed in the Famous section, she did not receive diagnosis until she was in her thirties and until then lived in a state of perpetual bewilderment and trauma about what was going on with her body. Some of Us Just Fall is an intelligent examination of the major aspects of chronic illness—pain, the search for answers, diagnosis, management, treatment, the feeling of being lost at sea. Atkin weaves this in with some of the best nature writing I have ever read, focusing specifically on where she has lived most of her adult life, the English village of Grasmere in the Lake District. She uses the unknowableness of nature, of human history within nature, to illustrate the mysteries of the body, focusing on misunderstandings, limits and how we often cannot see what is right in front of our face. This reminded me of Foucault’s theory of history, that the social construction of the time we live in determines what we are “allowed” to know.

Atkin explores, in a way that was both painful and moving, the work of chronic illness. The heartbreaking attempts to find help, to understand, that go nowhere. Told at one point, before receiving her hEDS and haemochromatosis diagnosis, that she had a psychiatric issue (conversion disorder) causing her to only think her body is malfunctioning and in pain, she throws herself into cognitive behavioural therapy whole heartedly, willing to try anything that might help. Of course it does nothing to help. Atkin discusses at length the work of the sick, the mistrust doctors and society has for the sick and disabled, and how one must perform “appropriate” illness that conforms to people’s strict and unforgiving ideas of what sickness is, or else you will not be able to receive care from those around you and the help you need from the medical establishment. The brief is simply this: don’t sound too knowledgeable to the doctor or too clueless, don’t to be too insistent, don’t ask for too much, don’t be in too much visible pain but also don’t be in not enough pain, use a polite, interested, obsequious tone of voice, never ever be angry or snap or weep, but you should cry sometimes a little?, don’t be too grateful but also don’t be not grateful, keep a positive attitude and never despair, but don’t have too many visible good days or else be considered a faker—always, always stay in a perfect temperate Goldilocks zone of what other people think illness should look like. The incredible burden of constantly staging your sickness so you can be helped and supported while simultaneously being ill cannot be overstated. I remember once, in tears, after going through a harrowing physical mess, thanking a doctor who had helped me for “believing me”. The look of total mistrust and suspicion she shot me, I will never forget— as if I had taken my mask off and revealed myself to be some kind of hypochondriac monster just looking for attention, though in actuality I was a very sick person who desperately needed support. I knew because of that one mistake of language she would be less willing, if not completely unwilling, to help me in the future. My wrist had been slapped, I hadn’t performed illness correctly.

There is so much in his memoir that is fascinating, like Atkin’s breakdown of “the nature cure”, the idea that if sick people would just get out into nature, nature will heal us. Atkin, a nature writer and poet who lives out in the country, has a lot to say about why this is, of course, total bullshit but also why sick and disabled people experiencing nature, and having access to it, is important for other, better reasons. The language of this book is immersive and rich, full of beauty in the face of horror, it is eloquent and affecting. If you love a sick person, I would highly recommend reading this book. It will open up your mind and will mean a lot to the person you love who is ill. If you are sick, this is on my very short list of the most affirming books I’ve ever read alongside How to be Sick by Toni Bernhard and Run Toward the Danger by Sarah Polley.

Famous

Strong Female Character is a memoir by a comedian, Fern Brady, but I would not suggest it to anyone looking for a comedic memoir. This isn’t Dave Barry waffling on about an amusing mixup that happened on his holiday. While Brady is a funny and intelligent writer, this book is advocacy, not jokes. Brady makes it clear from the outset that her mission in writing this book is to help other people who either have, or are looking for, an adult autism diagnosis. It is a review of her life through the lens of what she knows now, that she is autistic, and trying to make some sense out of the things that happened to her. Strong Female Character is a pretty brutal reading experience, which will probably not surprise people who have suffered throughout their lives with undiagnosed autism. There is a lot of abuse and trauma in this book, much of it stemming from how misunderstood and mistreated Brady was by those around her and how she misunderstood herself, as she had no way to access the tools and support she needed growing up.

A few years ago a close friend of mine said she’d been watching videos online about autism and thought she might be autistic, that it explained a lot of behaviours and feelings she’d had throughout her life, such as a feeling of not belonging to this world. This baffled me. “You’re not autistic,” I told her. “Everyone feels like they’re an alien or a monster in a human suit, it’s called the human condition. You’re empathetic, you make eye contact, you have a lot of friends and do social stuff. Why do you need this? Can’t you let this go?” I thought she should get off TikTok and was perhaps going a little pandemic stir crazy. My friend did not listen to me and continued to pursue and achieve diagnosis, later confronting me about my behaviour. As we discussed it, I watched my dismissiveness unravel before me in real time and offered her a heartfelt apology, which she thankfully accepted.

Looking back, I am somewhat confused by why that was my initial response. It seems really stupid to me now and very randomly judgemental of someone I respect and trust. I’m disappointed in myself, I thought I was more enlightened than I was. I suppose ableism cuts deep, even for people who are chronically ill, disabled, queer or otherwise othered! Brady addresses this in her book, that even as she pursued diagnosis and was diagnosed, she was upset when the diagnosis became reality. Her first reaction was anger and embarrassment, that she did not want to be some weirdo “chewing on stimming tools in public” who made autism into her entire personality. As an elder millennial, my conception of autism was pretty limited. Growing up, one of my close friends had an autistic brother who was non-verbal and would never be able to live independently—he was the only diagnosed autistic person I had ever met. As I got older and terms like “on the spectrum” and “Aspergers” were thrown around, I knew people who I suspected might be “on the spectrum”, but their social awkwardness was pronounced, where as my friend, while introverted, seemed generally socially fluid to me. Brady herself was held back from diagnosis a number of times by failing to look the part, suspecting even as a teenager that she might be autistic, and bringing it up to a number of doctors. However, she was too beautiful, with too many boyfriends to be taken seriously in her concern.

An important aspect of Brady’s memoir is the effort and energy expended to mask, to appear “normal”, especially for autistic women, as women are socialised to conform and please much more aggressively than men are, and are in much more danger if they do not. This makes women, and trans and non-binary people socialised as girls, like my friend, harder to diagnose. Brady’s masking was so taxing that she would often suffer meltdowns, causing her a lot of anguish. This usually involved punching, kicking, destroying things and/or self harming. It wasn’t about being angry, Brady explains, it was about being rubbed so raw by the environments she was in every day, she needed a physical outlet for her burnout. Brady spent years googling “why do I smash my house up?” never finding any help or information and feeling crazy. Even after she was diagnosed with autism, all of the information on meltdowns she could find was for the parents of autistic children. This compelled her to discuss meltdowns at length in her memoir, in hopes of helping other autistic adults feel less alone and discover resources for managing it.

In addition to ableism, I think I felt confronted by my friend’s search for answers about herself. During that period of time I was wilfully ignoring my own worsening health and myriad of injuries, not really wanting to look for possible answers but rather just live in a stubborn stalemate with the tweeting bird in my brain crying out that something was wrong. “How much else can possibly BE wrong???” I remember thinking. I’d had enough, I did not want to know anymore, I’d rather just blame myself. I already felt snowed under by a barrage of medical terms and conditions, that every time I printed out and handed over my two sided sheet of medical info to any new doctor that I was somehow being further and further washed away. Less and less of me, more and more of the sickness. Though this only occurred to me upon reflection—you rarely notice in the moment you are taking some else’s life choices personally. If my friend was rooting through her life for answers, did that mean I would have to do it too? I was so tired.

Brady’s book, as Atkin’s book, is a reminder that answers are not a gold medal to hang around your neck in triumph, but are hard won, opening doors forward and backwards in your life, creating thresholds for both you and others to stumble over. It’s so obvious that Brady was autistic, all the signs were there from babyhood, but none of her caregivers knew what the signs were and instead forced her to fit a mould they made that they could understand—she was simply a bad egg. When my friend told me she was autistic, I painted her with a brush of my own choosing, complimenting my outlook at the time, rather than listen to what she had to say without prejudice. When you discover something about yourself, you will have to wade through all of your feelings about it, as well as everyone else’s bullshit, you will have to consider all of it again, all of yourself again, from scratch and there will be consequences to that. However, Brady, like my friend, came to the wise conclusion that access to resources, support, community, tools and a better understanding of yourself in the long term was worth the price of dealing with the complex realities of diagnosis.

I would recommend this book to anyone curious about autism or who loves someone with autism, Brady’s descriptions of her triggers gave me a much better understanding of what life with autism is like and what can happen to autistic people who do not get the help they need. However, I would like to add some words of caution. There is a lot of violence in this book, Brady endures extensive abuse from people who were in positions of authority or who were supposed to love and care for her, it can be hard to read. Brady also has a lot of unexamined fatphobia. This was disappointing as she expresses progressive views on disability, sex work and gender equality. I hope she will get there one day.

Fern Brady has a stand up special, Autistic Bikini Queen, coming out on Netflix on the 22nd.

Object of Desire

I’ve always loved, and wanted to own, a signet ring. Nobody in my family or anyone I’ve ever known has worn one (not upper crust enough!), so there’s a possibility this desire sprang from my love for the film The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999). There will be spoilers for both the movie and miniseries throughout. The signet ring plays an important symbolic role in Tom Ripley’s subsuming of the wealthy Dickie Greenleaf. I’m currently watching Ripley (2024) on Netflix. The bar was set high by the 1999 film, but this new adaptation starring Andrew Scott as Ripley is also very good. They are individual takes on the story, with emphasis on different interpretations or aspects of the characters.

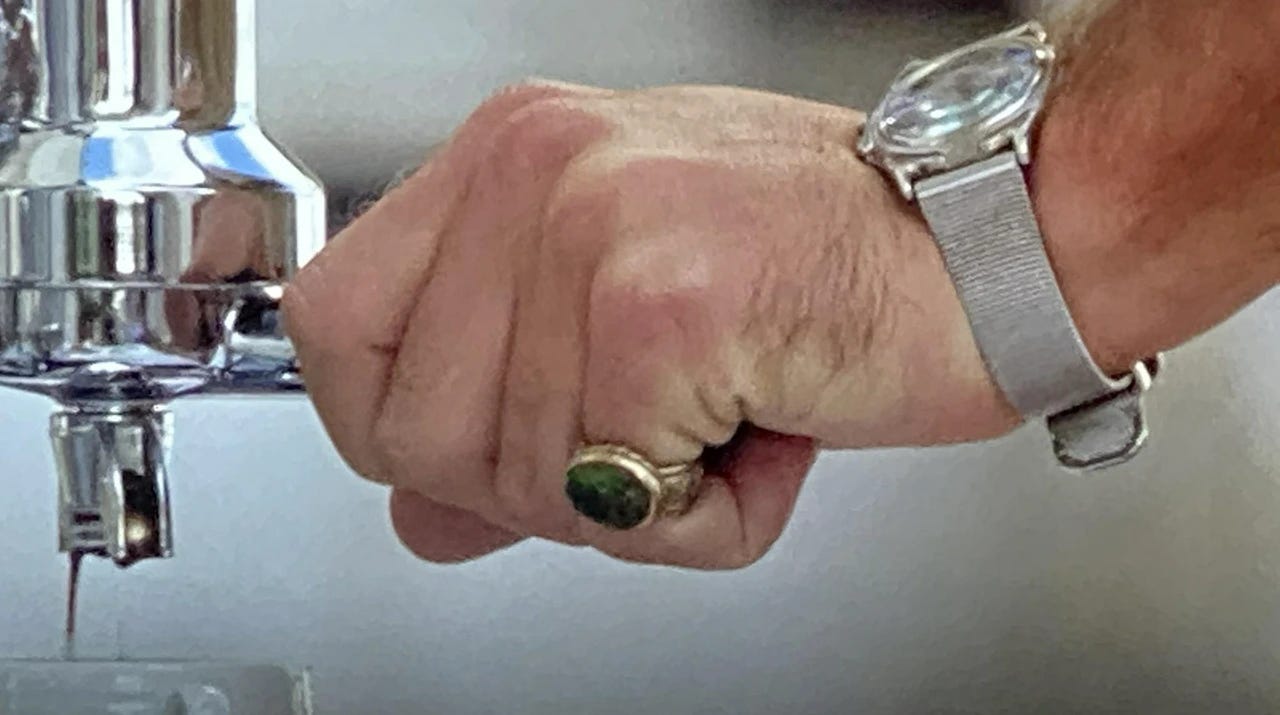

In The Talented Mr. Ripley, Matt Damon’s Ripley is sympathetic, a monster, yes, but perhaps one driven to such depths by class, queerness, loneliness and longing to belong. Jude Law’s Dickie (so beautiful you gasp every time he’s on screen) is a petulant, spoiled party boy. In Ripley, Tom Ripley is an aesthete and cold blooded sociopath. Johnny Flynn’s Dickie is kind and soft spoken, living off his family money, sure, but also searching for himself. Jude Law’s signet ring is a gift from girlfriend Marge (Gwyneth Paltrow), an interesting choice, and is chunky, gold and green with a protruding oval stone, worn on his pinky. Ripley comments on it right away, how much he likes it, and Dickie brushes off the comment. Marge jokes that the ring was cheap, she purchased it locally and had to haggle for it, joke being if it were actually cheap there’s no way Dickie would be wearing it. There looks to be etchings on it, though that’s never made clear and it is almost certainly, given their location, a valuable antique.

I could not find a good image of Johnny Flynn’s signet ring from the 2024 Ripley. The miniseries is in black and white, though it’s funny, I so clearly picture the ring as gold and deep red, those classic colours of wealth and royalty and desire. Johnny Flynn’s ring is less prominent than Jude Law’s, it’s smaller with a more subtle square stone and does not appear to have any etchings. It is also worn on his pinky. It is frequently noticed by other characters and lingered on by the camera much more than in 1999’s The Talented Mr. Ripley. Johnny Flynn’s Dickie covers it at times with his other hand, appearing a bit ashamed of it, presumably as it is such an open marker of his wealth and status, but one he’s not willing to part with—a family heirloom perhaps. In Ripley, after Tom kills Dickie, removing this ring (lubing it off Dickie’s finger with his own blood!) and putting it in his pocket is one of the first things he does. After he has taken Dickie’s identity, he wears it with relish. The signet ring in Ripley is similar in style to the one seen below.

These two rings—a bulky, fancy signet ring on Jude Law’s extravagant playboy Dickie, and an elegant, subtle signet ring on Johnny Flynn’s gentle, aimless rich kid—are artful symbols of the characters themselves, and of what Tom Ripley, in each version of this story, desires to steal from Dickie. Not just the jewellery, but the essence of who Dickie is. The signet ring is a way to suck out his soul. In The Talented Mr. Ripley this is driven by Tom’s love for Dickie, and in Ripley it is driven by Tom’s emptiness, ghoulishness— he is a body snatcher.

In the 1955 book, The Talented Mr. Ripley, Tom meets Mr. Greenleaf, Dickie’s father and gets the job to go after Dickie in Italy, immediately noting Mr. Greenleaf’s gold signet ring with its worn down crest. Later on he notes Dickie’s own signet ring is even bigger and fancier than his father’s. It is, in fact, in a moment of reflecting on the signet ring that Tom realises he is going to kill Dickie.

Tom sat opposite [Dickie], staring at his hands with the green ring and the gold signet ring. A crazy emotion of hate, of affection, of impatience and frustration was swelling in him. He wanted to kill Dickie. It was not the first time he had thought of it. He had failed with Dickie, in every way. He hated Dickie. He had offered Dickie friendship, companionship, everything he had to offer, and Dickie had replied with ingratitude and now hostility. If he killed him on this trip, he could simply say that some accident had happened. He could—He had just thought of something brilliant: he could become Dickie Greenleaf. The danger of it, even the inevitable temporariness of it, only made him more enthusiastic. He began to think of how. — Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Mr. Ripley

The term ‘signet’ comes from the latin for ‘sign’— a signet ring is an indisputable sign of who someone is, particularly in a legal sense. It is classically worn on the pinky, but can also be worn on the index or thumb, and has an engraving unique to the person wearing the ring. This engraving could be stamped into wax, clay or ink to mark their identity. The signet ring predates the signature and were worn by those with power and wealth. Having your personal marker on your finger means it can always be with you and can be used by no other. When one is made to ‘kiss the ring’, it is the signet ring to which this phrase refers, the signet being as one with the person wearing it. The carving of one’s name or a family symbol into a ring goes back at least as far as the Mesopotamians in 3500 BC. Ancient Egyptians, Romans, Greeks, all used signet rings. Traditionally, the signet ring would be smashed upon a person’s death (they still do this when the pope dies) as much havoc could ensue if you got ahold of someone else’s signet ring.

Early signet rings were carved in relief, meaning the image on the ring was raised, and, if containing words, were carved on backwards as to be legible when imprinted into substances. This took a lot of skill to make. As society moved into the early modern period and more people could read and write, signatures took the place of signet rings, though as a fashionable statement piece, they remained. They became more elaborate and were now safe to be passed down as heirlooms, as they were just for style and symbolism. Today they are often made without engraving, though to me a real signet ring will always be engraved with something and worn on the pinky. However, these rings have retained their association with the upper classes. So you can see why a signet ring was really the perfect choice of jewellery for Dickie to wear and for Tom to usurp. Tom going out and getting his own signet ring just wouldn’t have the same effect or meaning!

Here’s some cool antique signet rings:

For anyone curious-- I tried to watch Fern Brady's standup special and I did not like it at all!